[One to four stars. Four sentences each. No spoilers. Sources: Criterion Channel, HBO Max, Hulu, Internet Archive, TCM, YouTube.]

Two on Bunker Hill

Chicago Calling (dir. John Reinhardt, 1951). One of the bleakest films I’ve ever seen, with Dan Duryea, in what must be his finest performance, as Bill Callahan, a hard-drinking failed photographer living in Los Angeles’s impoverished Bunker Hill neighborhood. Bill’s wife gives up on him (with good reason) and leaves with their young daughter — and then things really go wrong. The element of contingency, signaled in an opening voiceover, is strong: Bill’s chance encounters with strangers, notably a telephone repairman and a boy with a bicycle (Gordon Gebert from Holiday Affair), shape his future. The movie seems influenced by the neo-realism of Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1949), and our household wondered whether Chicago Calling might in turn have influenced De Sica’s Umberto D., released a year later. ★★★★ (IA)

Night Has a Thousand Eyes (dir. John Farrow, 1948). Not a horror movie (as it’s often described): I’d call it supernatural noir. Edward G. Robinson plays John Triton, the Great Triton, a stage mentalist (think Stanton Carlisle in Nightmare Alley) who discovers that his powers have suddenly become real. Thus Triton is able to foretell tragedies that are inevitable, however he might try to avert them. But try he must, even relocating to Bunker Hill to do so. Gail Russell is memorable as the young woman who may be doomed by the Great Triton’s prediction. ★★★★ (YT)

*

Two by Joseph Losey

M (1951). A remake, moving Fritz Lang’s movie to Los Angeles, where the police and the criminal underworld both seek the child killer who’s terrorizing the city. It’s a deep cast, with Luther Adler, Walter Burke, Raymond Burr, Howard Da Silva, Norman Lloyd, David Wayne (the agonized killer), and many other non-stars. The movie makes great use of the city, with a shot from inside Angels Flight as the story opens, and a long, long episode in the Bradbury Building, the movie’s Best Supporting Actor. Creepiest moment: the shoes. ★★★★ (YT)

The Intimate Stranger (dir. “Alec C. Snowden,” 1956). Losey, blacklisted in the States, makes a film about a blacklisted film editor, Reggie Wilson (Richard Basehart), who has moved to England from the States after an affair with his boss’s wife ends his Hollywood career. Reggie finds his new life undone by letters from one Evelyn Stewart (Mary Murphy), who hopes that Reggie can still make time for her even though he’s married. Who is this woman, and why, if Reggie doesn’t know her, does her have train tickets to Newcastle in his pocket? Basehart presents as a more capable William Shatner; Murphy and Constance Cummings (as a star abroad) are dazzling; and the meta ending, with a fight on a film set, is deeply satisfying. ★★★★ (YT)

*

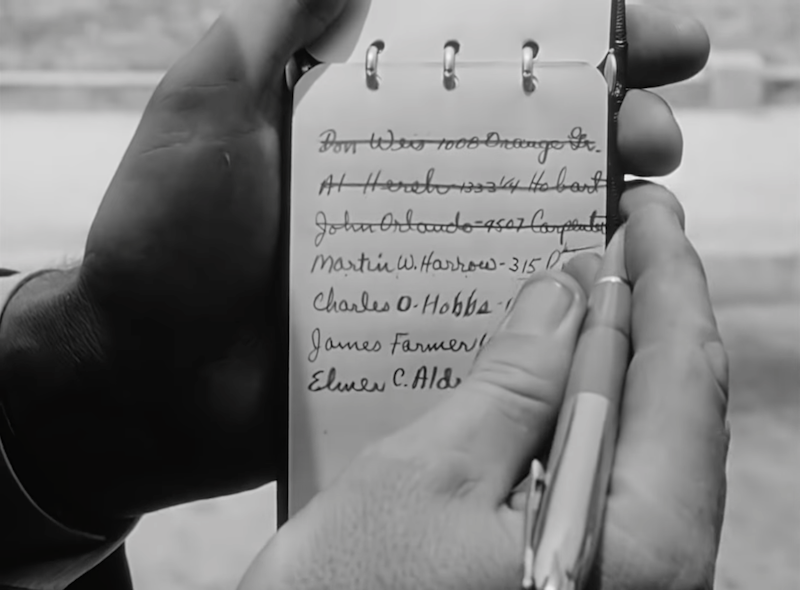

Open Secret (dir. John Reinhardt, 1948). In town for a short stay with an old friend, newlywed couple Paul and Nancy (John Ireland and Jane Randolph) stumble onto the murderous doings of a gang of anti-Semites. A surprisingly good low-budget movie, taking place mostly in one small apartment where every knock on the door, every ring of the telephone, threatens danger. Reinhardt goes all in on film noir: we almost never see daylight, and even a little camera shop is open late into the night. The anti-Semites’ talking points about “foreigners” and a “movement” make this movie eerily contemporary. ★★★ (YT)

*

The Cocoanuts (dir. Robert Florey and Joseph Santley, 1929). We gave up on The Big Store a few nights before, so we tried the Marx Brothers’ first full-length movie, with much better results. The setting is Florida during a real-estate boom, with Groucho as a hotel manager, Chico and Harpo as casual thieves, and Zeppo as the manager’s assistant. Adapted from the stage musical (George S. Kaufman–Irving Berlin), with pre-Code innuendo, unnecessary song-and-dance interludes, Chico’s and Harpo’s instrumental interludes, the “why a duck” routine, a great bit with musical doors, and Margaret Dumont. ★★★★ (CC)

*

Scotch: A Golden Dream (dir. Andrew Peat, 2018). A documentary that is at heart a long commercial for single malts, especially Bruichladdich. Much pontificating and promoting and storytelling from brand ambassadors and “master distillers” (a term one on-camera expert calls into question), but scant history, and no attention to basic matters: coloring vs. no coloring, single malts vs. blends. The location is the island of Islay, but there’s not a word about Laphroaig — did that distillery opt out? I take much pleasure in a couple of ounces of Bruichladdich or Glenmorangie or Cutty Sark, and I take no pleasure in writing these disappointed sentences. ★★ (H)

[And the director is named Andrew Peat? For reals?]

*

Shakedown (dir. Joseph Peveny, 1950). Howard Duff as Jack Early, a glib, cocky, manipulative newspaper photographer on the rise. Why, he manipulates more people than a chiropractor, even cueing a desperate woman when to jump from the window of a burning building so that he can get a good shot. But when Jack uses incriminating photos to shake down hoods (Brian Donlevy and Lawrence Tierney), there will be blood. I liked the scenes at the San Francisco newspaper, where we see Peggy Dow as a modern working woman (very modern: she goes away for weekends to see her boyfriend in Portland). ★★★★ (YT)

*

When We Were Bullies (dir. Jay Rosenblatt, 2021). The premise might be good for a segment of a This American Life episode: filmmaker recalls a fifty-years-ago incident in which he and fellow Brooklyn fifth-graders bullied a classmate (an incident he already made brief use of in a previous documentary) and now tries to work out what happened. But the ethics of this venture are a shambles: in undertaking the work of the film, Rosenblatt chooses not to contact his bullied classmate, whose childhood self becomes the subject of withering commentary by the classmates Rosenblatt tracked down for interviews. I’d call that Bullying 2.0, and there’s nothing in the letter Rosenblatt finally writes to his classmate (the movie’s not about you; it’s about us) or in the self-serving conclusion that “everyone carries pain” that moves me to change my mind. This exercise in self-congratulatory narcissism deserves no stars. (HBO)

*

Two by Hugo Haas

Strange Fascination (dir. Hugo Haas, 1952). The director’s name was familiar, and it turns out that we’d seen at least one of his films (Lizzie). This one is a variation on The Blue Angel, with director Haas as Paul Marvan, a European concert pianist making a career in the United States. Diana Fowler (Mona Barrie), a dignified older woman with eyes for Paul, happily becomes his patron. But Paul has eyes only for Margo (Cleo Moore), a much younger woman, a dancer, a bleached-blonde (she admits it), and you already know that none of this will turn out well. ★★★ (YT)

Pickup (1951). Here the director plays Jan Horak, a railroad dispatcher who meets and marries one Betty, a much younger (again blond) woman in need of money (Beverly Michaels). There’s a boyfriend, Steve, hanging around (Allan Nixon), and we’re soon headed toward a low-budget The Postman Always Rings Twice. Jan’s sudden deafness and the equally sudden return of his hearing contribute mightily to the plot. Worth watching for Haas’s pathos, for Michaels’s viciousness, and for the chance to wonder what made Haas repeatedly take up this theme. ★★★ (YT)

*

Good News (dir. Charles Walters, 1947). It’s college as recreation for mostly rich white kids, singing, dancing, playing football, and partaking in hijinks. In 1947, when the G.I. Bill was reshaping the idea of college (at least for some veterans), this movie must have looked like a picture of a lost world. June Allyson is a good singer (I had no idea); Mel Tormé is a great singer (I knew that); Peter Lawford speaks excellent French. And Joan McCracken is lit. ★★★★ (TCM)

[Joan McCracken is lit.]

[Joan McCracken is lit.]

Related reading

All OCA movie posts (Pinboard)