The New York Times has a strange and compelling story today, “Redemption of a Lost Prodigy,” by Alex Vadukul, about Saul Chandler, a seventy-year-old boat builder who, as Saul Robert Lipshutz, was once a violin prodigy. Both Elaine and I are skeptical about this story. There is indeed a Saul Robert Chandler with addresses in Manhattan and Miami Beach: that makes sense for someone devoted to boats and sailing. And the Times ran a wedding announcement in 1975 with a Saul Robert Chandler who changed his name from Lipshutz. Mr. Chandler née Lipshutz is real.

Elaine’s skepticism is founded on her knowledge of all things musical. She finds details in the account of SRL’s studies improbable. And she finds utterly implausible the dramatic scene in which SC opens his violin case and plays his instrument for the first time in fifty years. Fifty years! The violin’s strings would have unraveled, she says, and the sound post would likely have fallen.

My skepticism is founded on the absence of any record of SRL as prodigy. Vadukul writes that SRL performed in Town Hall and Carnegie Hall before turning eleven, yet the Times archive has no evidence of these performances or of any others. And back then, the Times reviewed everything: in 1956, for instance, performances by the twelve- and then thirteen-year-old violinist Paul Zukofsky at the Juilliard School and Carnegie Hall received lengthy reviews — with photographs, no less. But nothing for SRL.

The Times article includes a photograph of SRL credited to the Paterson Evening News Photo Collection, via the Passaic County Historical Society. The finding aid for that collection lists a candid April 15, 1960 photograph of Saul Lipschutz. But there’s nothing in the Times with that name either.

I did find one bit of evidence for a performing career, an announcement in the Madison News, a New Jersey paper, preserved at Newspapers.com:

[“Friends of Fairleigh Dickinson Chamber Ensemble will present Bach’s Brandenberg [sic] Concerto No. Five with Saul Lipschutz, New Providence high school student, as violin soloist.” March 28, 1963.]

So there’s every reason to think that SRL played the violin. But we’re a long way from Carnegie Hall. There’s nothing more at Newspapers.com that would document the career of a prodigy: nothing for Saul or Saul Robert or Saul R., nothing for Lipshutz or Lipschutz. And though the Times article quotes musicians who remember SRL and speak highly of his playing, none of them describe him as a prodigy.

I don’t know what to make of the Times article. But I’ve begun to wonder about a March 29 tweet by the writer: “Story tease. For Sunday NYT, a story I spent some months on. At times, I felt like I found my Joe Gould.”

Alex Vadukul has to know that Joe Gould was a master fabulist, doesn’t he?

*

April 1: Elaine has shared her thoughts about this article: What to believe? And I’ve written to the Times.

*

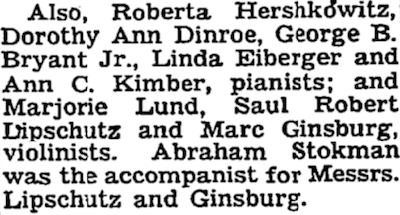

February 28, 2022: For whatever it’s worth, the Times Archive now returns an article that mentions Saul Robert Lipschutz at Carnegie Hall. From May 10, 1959, ”League Winners Heard in Concert; Two Programs Presented by Music Education Group at Carnegie Recital Hall.” Lipschutz was one of forty-one young musicians divided across two group recitals presented by the Music Education League.

Why update? This post, now four years old, still gets visits. And if participation in a group recital is what it means to play Carnegie Hall, the gist of the Times story is still in doubt.

Saturday, March 31, 2018

Who is Saul Chandler?

By

Michael Leddy

at

9:03 PM

comments: 10

![]()

Recently updated

Goodbye to all that The University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point is rethinking its plan to destroy study in the humanities.

[“To destroy study in the humanities”: no, that’s not an exaggeration.]

By

Michael Leddy

at

8:50 AM

comments: 0

![]()

From the Saturday Stumper

A clever clue from the Newsday Saturday Stumper: 3-Down, seven letters, “Training vehicle.” TRICYCL — no, that won’t work. And a clue that taught me something, 61-Across, ten letters, “Designer with feathers.” No spoilers. The answers are in the comments.

Today’s puzzle is by Andrew Bell Lewis. Difficult but doable.

By

Michael Leddy

at

8:38 AM

comments: 1

![]()

Friday, March 30, 2018

NYT, sheesh

From The New York Times: “Unlike her boss, attention from the news media was never something she sought.”

Related posts

All OCA sheesh posts (Pinboard)

By

Michael Leddy

at

12:58 PM

comments: 0

![]()

FKB pencil sharpener

[James Anderson (Robert Young) installs a necessary household tool. Click for a larger view.]

Face it: if father really knew best, there would have had a pencil sharpener up and running in season one, episode one. This sharpener didn’t make it onto the kitchen wall until the sixth and final season of Father Knows Best. In the episode “Bud, the Willing Worker” (December 7, 1959), Jim installs the sharpener without saying a word about it. Kathy sharpens a pencil in “Turn the Other Cheek” (December 14, 1959), after which the sharpener disappears from the wall where it so briefly had a home.

By the way, it’s National Pencil Day. Start your sharpeners.

Other FKB posts

“Betty’s Graduation” : Flowers knows best : “Margaret Disowns Her Family” : Scene-stealing card-file : “Your dinner jacket just arrived” : “A Woman in the House”

By

Michael Leddy

at

8:38 AM

comments: 0

![]()

Domestic comedy

“It’s like Sex and the City , but without the sex and without the city.”

Related posts

All OCA domestic comedy posts (Pinboard)

[“It”: the television series Gidget, whose main character is also a narrator.]

By

Michael Leddy

at

8:37 AM

comments: 0

![]()

Thursday, March 29, 2018

Lost in the city

I was about to see a movie with my friend Luanne and two other people unknown to me. Right before going into the theater, I went out to buy a pack of cigarettes. I walked up to a counter: “A pack of cigarettes,” I said, like someone in a movie. No brand — I was out of practice. The clerk came back with Pall Malls in a white hull-and-slide package. The words “Made with Broham Strings” appeared below the brand name. “How much?” $6.53. I paid with a ten and got my change and two books of matches.

Then I was walking outside, on a campus, looking for a place to smoke and observing several unbranded fast-food joints with all-glass exteriors. A giant with a long white beard and a cape was walking the campus. Everyone stared at him and whispered. And then I was walking in a version of Manhattan, with empty narrow streets at once dark and brightly lit — something like the alley in On the Waterfront where Terry and Edie run from a truck. I knew I was on the Lower East Side, but the street layout was baffling — Avenue A was followed by Second Avenue A. Which way was uptown? Which way was west? I couldn’t tell.

Then I was in a carpeted hallway on the second or third floor of an empty building. A man was carrying furniture up the staircase. I asked if he knew which way was west, but he spoke only Italian. “¿Dónde oeste?” I tried. I got the man to walk with me to a streetcorner in the hope that he could orient me, but once there, he couldn’t.

And then I thought to text Luanne and tell her I’d be really late. “I went out to buy cigarettes and am now being baffled by the Lower East Side,” I wrote, or something like that. I began to walk and reached the intersection of Harvard Avenue, Harvard Street, and Mechanic Street. And there was Luanne, on the other side of one of these streets, about six lanes of traffic away. We needed to get the No. 83 bus, which was parked right there — but it took off and drove right past us. So we went into the theater, which was also a church, where the movie had already ended. It was a good one, Luanne said.

[Sources: Luanne and Jim’s recent trip to the opera. An article about 1950s and ’60s hangouts in my college town. The motto of one such place: “Drop in for Coke and smoke.” A 60 Minutes story about Giannis Antetokounmpo. A TCM showing of On the Waterfront. Thinking about the streets of my Allston, Massachusetts, grad student days. Above all, this passage from W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz. And possibly the crackers and Mahón cheese I had before going to sleep.]

By

Michael Leddy

at

9:31 AM

comments: 0

![]()

Lost in a city

Austerlitz is lost:

W.G. Sebald, Austerlitz, trans. Anthea Bell (New York: Modern Library, 2001).

The image of a language as a city comes from Ludwig Wittgenstein (whose eyes appear in a photograph earlier in the novel):

Our language can be seen as an ancient city: a maze of little streets and squares, of old and new houses, and of houses with additions from various periods; and this surrounded by a multitude of new boroughs with straight regular streets and uniform houses.Also from Austerlitz

Philosophical Investigations , trans. G.E.M. Anscombe (New York: Macmillan, 1973).

Austerlitz on time : Marks on time

By

Michael Leddy

at

9:26 AM

comments: 0

![]()

Wednesday, March 28, 2018

Marks on time

When his family’s house was requisitioned for use as a convalescent home during World War II, James Mallord Ashman hid the doors to the billiard room and nursery behind false walls. When the walls come down, Ashman enters the nursery for the first time in ten years:

W.G. Sebald, Austerlitz, trans. Anthea Bell (New York: Modern Library, 2001).

Also from Austerlitz

Austerlitz on time

[So many things in Austerlitz blur, purposefully so. The novel refers to both a nursery and nurseries. The walls comes down in “the autumn of 1951 or 1952,” when Austerlitz enters “the nursery” for this first time in ten years. Or nine? Or eleven?]

By

Michael Leddy

at

10:04 AM

comments: 0

![]()

From Beware of Pity

So much depends upon “the so-called ‘chancery double,’” “a folded sheet of prescribed dimensions and format,” “perhaps the most indispensable requisite of the Austrian civil and military administration”:

Stefan Zweig, Beware of Pity, trans. Phyllis and Trevor Blewitt (New York: New York Review Books, 2006).

I would like to know what those “so-called ‘guides’” looked like. They likely bear little resemblance to the present-day shitajiki.

Related reading

All OCA Stefan Zweig posts (Pinboard)

By

Michael Leddy

at

10:03 AM

comments: 0

![]()