Fresca suggested in a comment that virtual schools are to school as TV dinners are to dinner. Right on.

And that made me realize: the TV dinner and the virtual school proceed from the same model: one person, in front of a screen. Get out your laptop, or TV tray; it’s time for “school,” or “dinner.”

Wednesday, June 5, 2019

Schools and TV dinners

By

Michael Leddy

at

11:04 AM

comments: 4

![]()

“Constructed like the early stages

of the automobile”

There are many questions to be asked about engineers:

Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities. 1930–1943. Trans. Sophie Wilkins (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995).

Also from this novel

“At least nine characters”

By

Michael Leddy

at

8:29 AM

comments: 0

![]()

Virtual schools

The Washington Post examines the case for the “virtual school.” Conclusion: “It sure sounds good. As it turns out, it’s too good to be true.”

A related post

“Personalized learning”

[A “virtual school” is not a school. And “personalized learning” is utterly depersonalized.]

By

Michael Leddy

at

8:26 AM

comments: 2

![]()

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

“Which dinner isn’t a Swanson?”

[Life, August 22, 1966.]

Click either image for larger servings.

I hadn’t thought about TV dinners in years. And then I listened to an episode of 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy. The Swanson TV Dinner had only slight representation in Life. But, fittingly, there were also commercials.

By

Michael Leddy

at

1:26 PM

comments: 0

![]()

50 Things

An excellent podcast from the BBC: Tim Harford’s 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy. Each episode (and there are more than fifty) is short and ultra-informative, with a list of sources on the podcast’s website. Concrete, cellophane, TV dinners: what will they think of next?

By

Michael Leddy

at

1:02 PM

comments: 1

![]()

“At least nine characters”

The narrator says that it’s wrong to “to explain what happens in the country by the character of its inhabitants”:

Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities. 1930–1943. Trans. Sophie Wilkins (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995).

Elaine and I are climbing Mount Musil, in two volumes, no lines, no waiting. See also Mount Proust.

By

Michael Leddy

at

8:52 AM

comments: 0

![]()

Monday, June 3, 2019

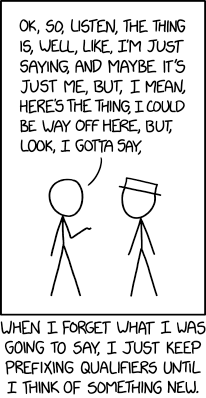

“Qualifiers”

[“Qualifiers.” xkcd, June 3, 2019.]

Personally, I’d suggest not skipping the mouseover text.

By

Michael Leddy

at

2:08 PM

comments: 0

![]()

How to make an Old Fashioned

Here is a demonstration — apparently not a parody — of how to make an Old Fashioned. Was someone confusing the Old Fashioned with the Mint Julep? Muddled mint, yes. Muddled cherry and orange, no. A tumblerful of bourbon, no.

Here is a more reliable guide to the Old Fashioned:

Shake 2 or 3 dashes of Angostura, then a splash of seltzer, on a lump of sugar. Muddle, add 2 cubes of ice, a twist of lemon peel, and a cherry, if desired. Pour in 1 1/2 oz. of your favorite liquor, stir well and serve. (Simple syrup in place of the lump sugar eliminates muddling and makes a much smoother drink and if simple syrup is used, you don’t need the seltzer.)I’ve had this little (4 11/16 × 2 3/4) mixing guide forever. I think of it as a passport to a lost world, one in which people ordered a Gin Daisy or a Jack-in-the-Box and bartenders knew what to do. I certainly wouldn’t. But I do know how to make an Old Fashioned.

The Old Fashioned family circle is a large one. Try Rye, Bourbon, Scotch, Rum, Apple or Irish — each one represents a cordial invitation to the appetite.

Professional Mixing Guide: The Accredited List Of Recognized And Accepted Standard Formulas For Mixed Drinks. (Elmhurst, NY: Angostura-Wuppermann, 1961).

By

Michael Leddy

at

2:02 PM

comments: 3

![]()

Twelve movies

[One to four stars. Four sentences each. No spoilers.]

The Green Book (dir. Peter Farrelly, 2018). Two excellent actors — Mahershala Ali as the pianist Dr. Donald Shirley, Viggo Mortensen as Frank “Tony Lip” Vallelonga, Shirley’s driver on a 1962 tour through the American south — stuck, alas, in a dreadful movie, full of clichés and cartoonish moments that permit no real consideration of the color line in American culture, or of what it might mean to live as a gay man on one side of that line. There’s a cringe-inducing insistence that each of the principals has something to learn from the other: “the doc” teaches Tony how to write good letters home; and Tony teaches “the doc” about fried chicken and R&B. What might be the corniest moment of all: Shirley, still in tails, sits down in a roadhouse to play Chopin before jamming the blues with the house band. It’s unfathomable to me that this film won the Oscar for Best Picture. ★★

*

Drive a Crooked Road (dir. Richard Quine, 1954). This was the Criterion Channel’s Columbia noir that I least looked forward to, thinking it would be about race cars. And it is, but only sort of. Mickey Rooney plays Eddie Shannon, a short, shy, horribly scarred auto mechanic and aspiring racer; Dianne Foster is Barbara Mathews, the glamorous woman who uses her influence to pull Eddie into a criminal scheme. Dig the mid-century modern interiors of the big party scene. ★★★

*

The Burglar (dir. Paul Wendkos, 1957). Not an especially good film, but an interesting one. Dan Duryea (b. 1907, playing a man who’s supposed to be thirty-five) engineers a jewel heist full of complications. Along

for the ride: an emoting gemologist, a dumb lug, and Jayne Mansfield (b. 1933) as a young woman who’s supposed to be just a few years younger than Duryea. Psychological hokum, snappy patter, location shots of Atlantic City and Philadelphia, and Martha Vickers in her next-to-last film appearance. ★★★

*

Experiment in Terror (dir. Blake Edwards, 1962). The experiment begins about twenty seconds after the opening credits end, and it never lets up, as a rapist and murderer (Ross Martin) presses a bank teller (Lee Remick) into stealing $100,000 — or else. Glenn Ford leads the FBI effort to catch the culprit. With excellent cinematography by Philip H. Lathrop, an atmospheric score by Henry Mancini, and strong HItchcock overtones (the bathroom and the ballpark). And in the Department of Wait, What?: this is the film that Blake Edwards directed just after making Breakfast at Tiffany’s. ★★★★

*

If Beale Street Could Talk (dir. Barry Jenkins, 2018). A story of familial love and romantic love, with two young people, Tish and Fonny (KiKi Layne and Stephan James), tangled in the cruelties and falsehoods of a criminal-justice system — make that a criminal justice-system. If Hollywood wanted to honor a film about color and American culture, this film, not The Green Book, would have been the appropriate choice. Or do films about color have to arrive at feel-good endings? The story this film tells (from James Baldwin’s novel) broke my heart. ★★★★

*

This Happy Breed (dir. David Lean, 1944). From a play by Noël Coward. The life of a married couple (Robert Newton and Celia Johnson), their children, friends and relations, joys and sorrows, minor and major, from 1919 to 1939. Very British (see the title, from Richard II), with stiff upper lips and many cups of tea. I wonder if this film might have been a secret influence on It’s a Wonderful Life: the Charleston scene got me thinking about that. ★★★★

*

The Room (dir. Tommy Wiseau, 2003). Rebecca Doppelganger, in Ghost World, evaluating the band at a graduation party: “This is so bad, it’s almost good.” Enid Coleslaw’s response: “This is so bad it’s gone past good and back to bad again.” Lacking the pep and pluck of an Ed Wood production, Tommy Wiseau’s cult film (starring Tommy Wiseau) seems to me just bad — banal, inane, stilted, witless, the product of a delusion of grandeur (see the moments of homage to James Dean and Orson Welles). This mysteriously financed story of love and friendship and betrayal is like dull outsider art. ★

*

The Disaster Artist (dir. James Franco, 2017). The story of The Room, with James and Dave Franco as Tommy Wiseau and best friend Greg Sestero (Johnny and Mark in The Room). Even a viewer who fails to see the appeal of The Room can enjoy this portrait of an auteur realizing his vision. My favorite moments: the movie premiere and the hilariously exact recreations of scenes from The Room. My favorite line, spoken by the auteur: “I have to show my ass or this movie won’t sell.” ★★★

*

Searching (dir. Aneesh Chaganty, 2018). A satisfying thriller with both predictable and unexpected and twists, as a father (John Cho) seeks clues to his daughter’s disappearance (Michelle La) by looking at what’s on her laptop and in her social media accounts. What makes the film unique is its approach to narrative: at every moment we ’re watching something on a screen: Facebook, Instagram, news reports, FaceTime calls, text messages, Google searches, YouTube videos, family photographs. It’s a highly inventive way to tell a story, one in which Set as Desktop Picture or Move to Trash takes on new and surprising meaning. Major props to Juan Sebastian Baron, Nicholas D. Johnson, and Will Merrick, the film’s cinematographers. ★★★★

*

On the Basis of Sex (dir. Mimi Leder, 2018). The early life and trials (pun intended) of Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Felicity Jones). A reductive story of triumph that feels like a made-for-TV movie, with a blue and brown palette and lots of cigarette smoke to let us known we’re in “the past.” Justice Ginsburg deserves better, and she got it: the documentary RBG (dir. Betsy West and Julie Cohen, 2018). Watch that instead. ★★

*

Moonrise (dir. Frank Borzage, 1948). What a strange movie, we thought, before realizing that a Criterion Channel glitch was slowing down the audio. But even with proper playback, it’s a gloriously strange movie, a bewildering love story set against a backstory of a murderous parent (“bad blood”). Dane Clark and Gail Russell star, but minor characters steal the show: Rex Ingram as Mose, a sage hunter straight out of Faulkner, and Harry Morgan as Billy Scripture, a mute man fascinated by mirrors and pocket knives. Hurrah for the Criterion Channel: here’s the real meaning of that overused word curation. ★★★★

*

Watch on the Rhine (dir. Herman Shumlin, 1943). It’s 1940 in Washington, D.C., and the story is something like Casablanca in reverse, though you’ll have to watch to understand (no spoilers). Bette Davis, Paul Lukas, and George Colouris are outstanding as the leads. The film moves very slowly at first, with some pleasant scenes of train travel; the tension later rises sharply, though not quite enough to counteract the deliberate dialogue and overall staginess. Screenplay by Dashiell Hammett, from the play by Lillian Hellman. ★★★

Related reading

All OCA film posts (Pinboard)

[There’s next to nothing said about in The Green Book about The Negro Motorist Green Book itself. If you’re curious, the New York Public Library can help. ]

By

Michael Leddy

at

8:06 AM

comments: 2

![]()

A Unabomber precursor

[Ross Martin as “Red” Lynch. Experiment in Terror (dir. Blake Edwards, 1962). Click for a larger view.]

He’s standing in front of a column in San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. His resemblance to the figure in the famous sketch is eerie and unmistakable. That’s Lee Remick to the left.

I highly recommend Experiment in Terror, available from the Criterion Channel.

By

Michael Leddy

at

8:05 AM

comments: 0

![]()